- Home

- Frances Reilly

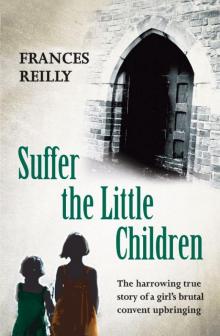

Suffer The Little Children

Suffer The Little Children Read online

Frances Reilly does not know when she was born. She spent the formative years of her childhood imprisoned within the walls of the Poor Sisters of Nazareth Convent and finally escaped with the help of a local MP. Having moved to England, she now lives in Colchester with her family.

Copyright

AN ORION EBOOK

First published in Great Britain in 2008 by Orion Books

This ebook first published in 2010 by Orion Books

Copyright © 2008 Frances Reilly

The right of Frances Reilly to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor to be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 4091 1123 8

The Orion Publishing Group Ltd

Orion House

5 Upper Saint Martin's Lane

London WC2H 9EA

An Hachette UK Company

www.orionbooks.co.uk

To protect the innocent, some of the names and details in this book have been changed. All the events described actually occurred.

To Josephine,

for your friendship.

This book is for us both.

Contents

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Prologue

Chapter 1: The Arrival

Chapter 2: Juniors

Chapter 3: Josephine

Chapter 4: The Saturday Routine

Chapter 5: The Lord’s Work

Chapter 6: The Visitor

Chapter 7: My Dead Dad’s Feet

Chapter 8: Christmas

Chapter 9: The Farm

Chapter 10: The Swing

Chapter 11: The Family

Chapter 12: Doubting Thomas

Chapter 13: The Inspectors

Chapter 14: The Cubbyhole

Chapter 15: Gifts on the Run

Chapter 16: The Premonition

Chapter 17: Back From the Farm

Chapter 18: Taking on a Senior

Chapter 19: A Strange Relationship

Chapter 20: The Nuns’ Pets

Chapter 21: Stowaways

Chapter 22: Breaking Out

Chapter 23: The Remand Home

Chapter 24: Rebelling

Chapter 25: The Top Window

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

To my sons Darren and Christopher – thank you for all your encouragement and support during the process of writing this book. It meant a lot to me.

To my granddaughter Ellisa – thank you sweetheart for all your support and for sending all the good luck cards and text messages. I love you x

To my grandson Kieran – thank you my wee darling for having loads of faith in me and for all your support and kisses. Love ye lots x

To Kevin Young, my ex-husband and very good friend – I can’t really thank you enough for all your encouragement and support with the court case and this book. Your hard work and advice at very stage of the book have been invaluable.

To Ann-Marie Hanna – thanks for your support with this book and for having the strength to come forward as a witness. I hope this book does not bring back too many bad memories.

Special thanks also to my agent Robert Smith for your complete belief in me and in the book, and for your determination and passion to see it published. Thanks also for your continued advice and friendship.

To Rebecca Cripps – thanks for all your help with the editing of my book.

Many thanks to Amanda Harris and all the other dedicated people at Orion who helped with the publication of this book.

Special thanks to my counsellor Merril Mathews, for caring so much. Talking with you helped me to put everything into perspective; helping me move on with my life. Your warm, caring personality makes you a very special person.

To the two policemen at the Child Rape Unit in Belfast (you know who you are), thank you for your gentle understanding and for the respectful way you treated me.

Finally, thanks to my legal team in Belfast. With special thanks to my solicitor, Ceiran McAteer, for his mild manner, gentle understanding and for coming to my rescue. And to Emily, his secretary, for her hard work, continued support and for always being there at the end of the phone.

Frances Reilly

May 2008

Author’s Note

This is the true story of my childhood in care. My sister Loretta was six and I was two when our nightmare began, so the first chapter of the book is based on what she later told me; the rest I remember only too well.

PROLOGUE

‘Look at this, Frances,’ my ex-husband, Kevin, said, pointing to an article in the newspaper.

My eyes swam as I read the first paragraph. A group of women in Scotland were taking an order of nuns to court for abusing them during their childhood.

‘The Poor Sisters of Nazareth,’ I gasped. I felt dizzy and found it hard to breathe.

The Scottish women were taking action against the same order of nuns who had abused me for most of my childhood; some of the women were around my age.

Vivid, unwanted memories flooded into my mind. It didn’t feel like it had all happened more than thirty years ago; suddenly, it was all so fresh that it seemed like only months ago. Filled with panic, I found myself unable to read on, so Kevin read the article to me. As I listened to these women’s stories they all rang true to me, and I could feel their pain. I wasn’t surprised or shocked, as some readers might have been, and I really hoped that these women would be listened to and believed.

I’d left the convent a very damaged person, carrying with me a lot of emotional problems. I was often severely depressed and on many occasions contemplated suicide. There didn’t seem to be anyone outside the convent who understood what I was feeling. Because of the troubles in Northern Ireland, I didn’t come into contact with anyone who wasn’t a Catholic, and whenever I tried to speak out about the abuse I wasn’t believed. People didn’t want to hear a bad word said about the Catholic religious orders. No one back then would have gone up against them.

I learnt quite quickly to keep my mouth shut and to suppress my feelings. I tried to push all the bad memories out of my mind, to pretend that they hadn’t happened and to behave as normally as I could. This made it easier for me to be accepted in the Catholic housing estates where I was living at the time. I didn’t report the abuse to the police because I was sure they wouldn’t believe me, or wouldn’t want to know.

Once I accepted that people didn’t want to believe or hear what I was saying, I had to find a way to survive. Over time I developed two survival mechanisms. First, I tried to hide the most painful memories by putting on a front. Every day I was living a lie. On the outside I was outgoing and cheerful, but inside I never stopped hurting. Also, I erected barriers to stop people, except my children, from getting close and hurting me.

While my children needed me, these mechanisms worked well enough, although I struggled, especially with relationships. Sometimes it all became too much: the mask would slip, and I would sink into a deep depression. As my children became less dependent, my defences started to fail, and by the time they’d left home, they had collapsed completely. The memories I’d tried to bury returned to haunt me, and the barriers I’d erected be

gan to collapse. My life started to fall apart. Flashbacks to the convent became much more regular. I started to get frequent panic attacks and developed severe agoraphobia. I’d always suffered from periods of depression, but these became more pronounced.

My cleaning compulsion developed into obsessive-compulsive disorder; I exhausted myself by repeatedly cleaning and tidying, doing work that didn’t need doing; I imagined that germs were everywhere and that I had to protect myself and my family against them. I would panic if I ran out of bleach and nobody was about to go to the shops for me. If a family member moved one of my video cases so that it wasn’t in line with the others, it would be enough to upset me for the whole day. I would cry if a baked-bean can wasn’t neatly stacked on the correct shelf and facing outwards, and I shopped not for food but to restore order to my cupboards. I stopped eating properly and became anorexic. I was a mess. I became suicidal and knew that something had to change.

In January 1999, five months after reading the article about the Scottish women’s court case, I found the courage to go to a solicitor to try to seek justice. But after bottling my feelings up for so many years, I found it hard to choke out even the most basic description of what had happened to me. Instead, I just sat in his office and sobbed uncontrollably. I couldn’t find the words. Finally, after several visits, I managed to explain to him what had happened to me as a child. My fight for justice had begun.

CHAPTER 1

The Arrival

Omagh, Northern Ireland, December 1956

‘Shhhh!’ said Loretta. ‘Can ye hear something?’

My brothers and I fell silent. There were voices coming from the living room downstairs. Mammy was talking to someone – a man – but Loretta didn’t recognise his voice.

Christmas was coming, and Loretta had been telling us about the cards and presents she was going to make at school the next day. Now she was up and out of the camp bed we shared and tiptoeing across the room to the landing at the top of the stairs, where she could hear the voices more clearly.

‘Sure, I’ll pick yous up early in the morning, Agnes. Have the wee ones ready; it’ll be a long journey for them to Belfast,’ the man said.

Loretta skipped back into the room and slipped into bed beside me. ‘We’re going to Belfast tomorrow!’ she said excitedly.

None of us had ever been out of our small town of Omagh, some seventy miles from Belfast, so this was big news.

‘Sure, I knew yous must have been going somewhere, because me and Michael are going to our Aunt Mary for the day,’ Sean whispered.

He and Michael shared another camp bed in the same room. Sinéad, the baby, was in a cot next to us.

‘Why aren’t yous coming with us?’ Loretta asked, surprised.

‘I don’t know, sure,’ Sean replied.

‘Well, I hope our teacher lets me make Christmas presents another day,’ she said.

Suddenly, baby Sinéad started to cry.

‘Quick, settle down and go to sleep before Mammy catches us!’

It was still dark when our mammy woke us the next morning. Loretta helped me get washed and dressed in my favourite red trouser suit. She enjoyed helping me; it made her feel grownup. Meanwhile Mammy saw to Sinéad, who was eight weeks old and very demanding.

Loretta took me to the kitchen for breakfast, where Michael and Sean were just finishing up. They put their plates in the sink and grabbed their coats from the hallway.

‘See ye later on, sure,’ Michael shouted as he and Sean ran out through the back door.

‘Loretta! Watch the baby a wee while,’ Mammy said, laying Sinéad down on an armchair.

We listened to her footsteps as she dashed frantically from one room to another, dropping things along the way. By now I’d caught my sister’s excitement about the trip, even though the boys weren’t coming with us. At least we’d have a lot to tell them when we got back, Loretta said.

A car horn beeped outside. Mammy ran downstairs and waved through the kitchen window to a man standing next to a black car. Picking Sinéad up from the chair, she told Loretta to bring me outside.

The atmosphere was tense on the journey to Belfast. Our mammy was usually loud and chatty, but she hardly said a word. Loretta began to worry. Suddenly, everything about the trip felt wrong. Too young to pick up on the tension, I, on the other hand, was enjoying the ride. It was a long drive, and as we approached Belfast patches of fog began to obscure the way ahead, which slowed the driver down. Eventually, we came to a stop.

It was hard to tell if we’d reached the end of the journey. Peering through the car window, all we could make out was a high brick wall rising up through the fog. Loretta got out of the car, glad of the chance to stretch her legs. Mammy and the driver began an intense whispered conversation, which they abruptly broke off when Loretta reappeared.

Mammy got out of the car. ‘Hold on there to your wee sister,’ she said to Loretta, walking alongside the high wall.

Loretta grabbed me by the hand. Looking up, she noticed that there was broken glass sticking out of the top of the wall, with coils of barbed wire above that.

‘Maybe it’s a prison,’ she said as we rushed to keep up with Mammy.

We caught up with her just as she stopped at a big wooden gate built into the wall. It didn’t occur to Loretta that we’d be seeing what was on the other side, but something felt wrong all the same. She tightened her grip on my hand, and I yelped with pain. Mammy handed Sinéad to Loretta, who had to let go of me as she struggled to keep hold of the tiny infant in her arms.

‘Now, Frances,’ Mammy said, looking down at me, ‘stay close to Loretta. I’ll be back for ye soon. Loretta, give this to whoever answers the bell.’ She handed Loretta a letter and pulled on a cord hanging from the wall next to the gate. Then she dashed back to the revving car, which immediately drove off.

We watched in horror as the car disappeared into the distance, its exhaust fumes merging with the fog. I started to cry, shouting and screaming for my mammy to come back. Loretta stood next to me, shocked into silence, holding on tight to Sinéad. She couldn’t cry. She desperately wanted to, but the tears wouldn’t come. Instead, a cold, disabling numbness crept through her body. The rear lights of the car winked before they faded into the mist.

The gate in the wall opened with a heavy creak, and a woman said, ‘I’m Sister Lucius. Can I help you?’

We dragged our eyes away from the road. There was a nun at the gate wearing flowing robes. All that was visible under her habit and veil was her round Irish face, her cheeks red from the cold. Loretta handed over Mammy’s letter in silence.

‘I’ll be taking ye now to see the Reverend Mother. Follow me,’ the nun said. She locked the gate and led us through a deserted walled garden, walking briskly ahead of us with her arms tucked up inside her habit. An enormous redbrick building loomed up before us, and soon we came to a pair of doors with latticed panes, which opened on to a high-ceilinged lobby area just inside the building. Sister Lucius told Loretta to hand Sinéad over to her. Loretta desperately wanted to keep hold of her baby sister, but, powerless to argue, she did as she was told.

Tall marble statues of St Anthony and the Virgin Mary loomed over us as we passed through the silent, flower-filled lobby, which soon narrowed into a dim, gloomy corridor that seemed to stretch for miles. The air inside the corridor was thick with the smell of overcooked food. The dark, green-brown walls looked as though they were sickening for something. There was no one around. It was deathly quiet. As we edged our way along the cold stone floor, past locked wooden doors with big metal handles, Loretta still wasn’t convinced that we weren’t inside a prison. What was behind those doors? Where was everyone?

Finally, Sister Lucius came to a halt outside a huge door. She knocked loudly. ‘Enter!’ came the summons from the other side, in a tone of voice that would have sent a shiver down anyone’s spine, let alone a child’s. Loretta trembled at the sound of it. In we went. Sister Lucius closed the door behind us.

> We found ourselves in a room that resembled a small library.Leather-bound hardbacks lined the shelves, and small piles of books lay neatly stacked on wooden tables. Along one wall stood rows of filing cabinets and a long carved desk. Behind the desk, hunched over a book, sat a nun of obvious importance. After several minutes she raised her head and gave us a cold, appraising look. She had a penetrating stare, like a storybook witch’s. Judging by her expression, it seemed clear that she thought we were contaminated in some way.

Sister Lucius placed Mammy’s letter on the desk. The nun picked it up and began to read. I started crying again. Loretta stood next to me, feeling helpless and confused. The nun put the letter into a filing cabinet and turned towards us.

‘Come closer. I’m the Mother Superior,’ she said. ‘Your mother has expressed her wish for you to stay here with us and devote your lives to God.’ She paused, staring at us coldly. ‘We have a lot of rules for you to follow, and I suggest you learn them quickly. Anyone breaking the rules will be dealt with severely. First, before mixing with the other girls, you will need a bath. You will go with Sister Lucius now. I will see you all again later. And from now on you will address me as Reverend Mother.’

We followed Sister Lucius out of the room. As we walked along the corridors, she explained that we were in a convent that was also an orphanage for unwanted children and children whose parents had died and had no one else to look after them. The orphanage was called ‘Nazareth House Convent’, and the order of nuns was the ‘Poor Sisters of Nazareth’. Loretta didn’t yet know how apt her first impression of the convent had been. It was indeed a prison: a prison for children – young girls and babies – whose only crime was being born. The broken glass along the top of the walls was to keep us in, not the world out.

Suffer The Little Children

Suffer The Little Children